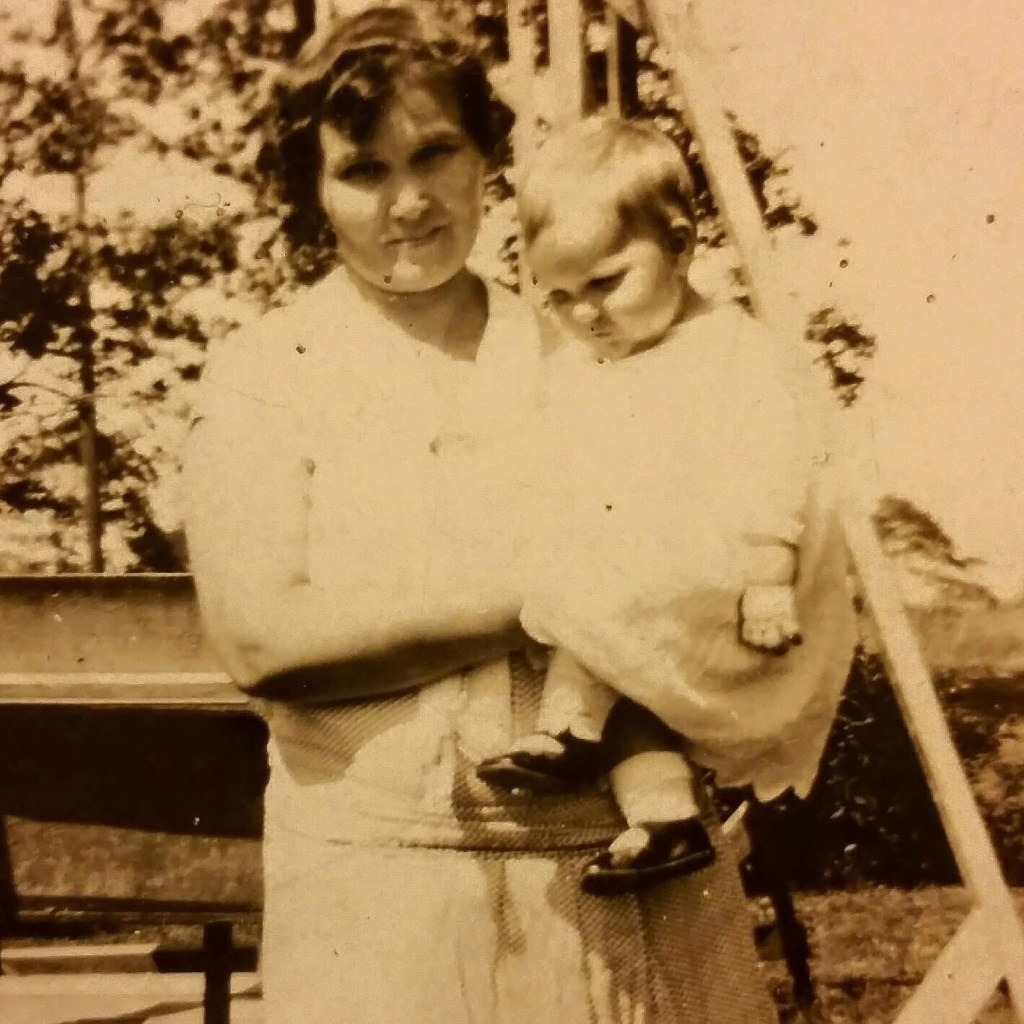

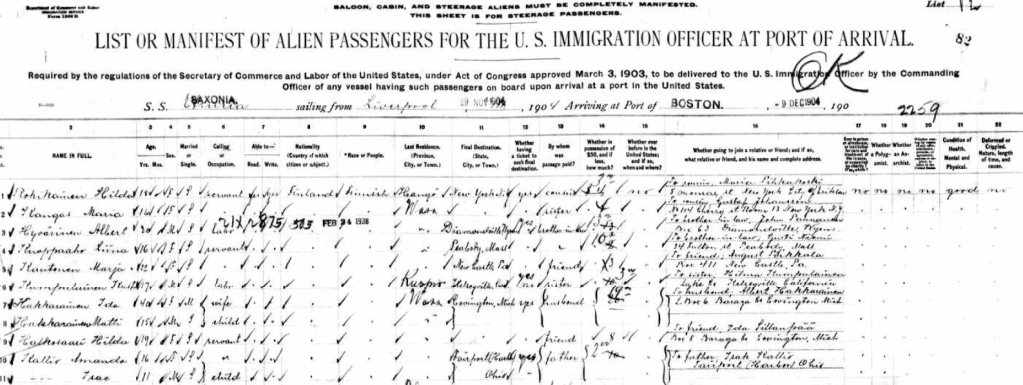

In 1904, Amanda Helen Kallio, a 16-year-old from Finland, boarded the Saxonia, a Cunard Line steamship, sailing from Liverpool to Boston. She was traveling with her 11-year-old brother Isaac and planned to join her father, Isaac Kallio, in Fairport Harbor, Ohio.

Local history pages published by Case Western Reserve record that “most Finns came to America from rural areas for economic reasons, while compulsory military service in the Russian Army also prompted many to emigrate. Large Finnish communities were established in Fairport Harbor, Ashtabula, Conneaut, and Cleveland, where manual labor was needed. Some immigrants were skilled. Finnish women were employed in domestic work, so that by 1916 Finnish women outnumbered men.”

You may recognize the name of that female Finnish immigrant above, dear reader. That 16 year old woman was my namesake and my great-great-great grandmother.

We are studying Game Theory during my Econ class, which I’m taking as part of an MBA at Baldwin Wallace University. It’s fascinating to me. Game Theory, the mathematical study of strategic decision-making, explores how individuals or organizations behave when their outcomes depend not only on their own choices but also on the choices of others.

My ancestor’s voyage was part of a larger economic drama – a transatlantic steerage rate war that exemplifies one of Game Theory’s concepts (and one I’ve been warned will be on my econ final): the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a classic example of game theory: two players must decide whether to cooperate or screw each other over (defect). It’s illustrated like this:

“Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of speaking to or exchanging messages with the other. The police admit they don’t have enough evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge. They plan to sentence both to a year in prison on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the police offer each prisoner a Faustian bargain. If he testifies against his partner, he will go free while the partner will get three years in prison on the main charge. Oh, yes, there is a catch … If both prisoners testify against each other, both will be sentenced to two years in jail. The prisoners are given a little time to think this over, but in no case may either learn what the other has decided until he has irrevocably made his decision. Each is informed that the other prisoner is being offered the very same deal. Each prisoner is concerned only with his own welfare—with minimizing his own prison sentence.”

Poundstone, William (1993). Prisoner’s Dilemma; New York: Anchor. ISBN 0-385-41580-X.

If both cooperate, they receive moderate benefits. If one defects while the other cooperates, the defector gains more while the cooperator suffers. If both defect, both lose out—highlighting how self-interest can lead to collectively worse outcomes.

This dynamic played out vividly in the 1904 steerage rate war among steamship companies. Cunard, White Star, Hamburg-American, and others slashed third-class fares from $25 to as low as $6 in a bid to outcompete one another. Each company hoped to capture more market share by undercutting rivals, but the result was a race to the bottom. Ships like the Saxonia were packed with immigrants, yet the companies lost money on every ticket sold.

Had the companies cooperated – maintaining higher fares – they might have kept profitability. But fear of losing passengers to competitors drove them to defect and undercut the competition. The result? Overcrowded ships, financial losses, and a surge of immigrants that strained Ellis Island and triggered public anxiety about “undesirable” arrivals.

It’s worth noting that my ancestor sailed on the Cunard steamer Saxonia in November 1904, arriving in Boston.

Had the price war not erupted, it’s highly likely the personal history of yours truly would be quite different. A price difference from $25 dropping to $6 was impossible to ignore. WWI-era draft registration records show at the time her father Isaac worked in the shipyards for the Great Lakes Engineering Works; estimates at the time state workers like him earned around $30 a week. Saving a weeks’ pay was just as important then as it is now, perhaps more so in a time before easy access to credit and organized social services.

The U.S. government responded with stricter immigration laws and enforcement. Steamship companies were fined for landing unqualified passengers and required to deport those rejected at inspection. Ironically, the very competition that aimed to boost profits led to increased regulation and reputational damage, this online article states.

Game Theory teaches that in repeated interactions, cooperation can emerge if players recognize the long-term benefits. Eventually, the steamship lines did reach a truce, restoring fares to sustainable levels. But the 1904 rate war remains a cautionary tale: when rivals act in isolation, chasing short-term gains, they risk mutual harm.

For Amanda Helen Kallio, the Saxonia’s voyage was a lifeline – a chance to start anew in America. For the companies, it was a strategic misstep. And for this MBA candidate, it’s a vivid illustration of Game Theory in action, played out not in a prison cell but across the Atlantic Ocean.

For more on the Prisoner’s Dilemma and how Americans broke the cycle on Black Friday, check out this podcast.